“Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.” – Helen Keller

As one of the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) 10 Big Ideas, NSF INCLUDES aims to broaden participation of underrepresented groups in STEM fields throughout the United States. The NSF INCLUDES Network is composed of a national network of NSF-funded Alliances and Design, Development, and Launch Pilots; industry and foundation partners; federal agencies; NSF-funded Broadening Participation in STEM programs; and other stakeholders such as faculty, students, professional associations, community organizations, and others engaged in broadening participation research.

To build this network, NSF funded a partnership of organizations (SRI International, EDC, Equal Measure, Westat, QEM, ORS Impact, and Digital Promise) to develop engagement and communication tools, shared measures, and channels for visibility and expansion. This infrastructure—the NSF INCLUDES Coordination Hub—balances expertise in broadening participation in STEM with technical knowledge about network engagement and expansion, measurement, research, evaluation, and communications.

Equal Measure’s role in the NSF INCLUDES Coordination Hub is to contribute expertise in communications and research, especially in the context of collective impact initiatives and systems change. The NSF INCLUDES infrastructure fosters collaboration through five design elements of collaborative infrastructure: shared vision, partnerships, goals and metrics, leadership and communication, and expansion, sustainability, and scale. We lead the Communications task area, and team members also participate in the Research and Shared Measures task areas.

Two years into the initiative, we’d like to reflect on several themes that have emerged from work in this multi-partner initiative: 1) Scope of work influences the size and capacity of the partnership structure; 2) Relationships and relevant experience unite the organizations; 3) Shared vision, values, and responsibilities align the work; and 4) Complementary skills and knowledge from staff of multiple organizations enhance learning and knowledge creation.

Scope of work influences the size and capacity of the partnership structure

Broadening participation in STEM requires a multifaceted, interdisciplinary strategy to identify and manage goals, activities, measurable outcomes, and knowledge dissemination. From the onset of the project, the Coordination Hub has continued to sharpen its role in broadening participation and “building a network to accelerate broadening participation.”

The Coordination Hub has clarified its scope of work to make its own collaborative infrastructure more effective and efficient. A broad proposition, by definition, relies on organizational staffing capacity and expertise to perform the work efficiently and effectively.

Within the Coordination Hub, one organization (SRI International) serves as the administrative and fiduciary leader, while the governance structure was designed for an organizational representative to act as a lead in different task areas—in our case, Communications.

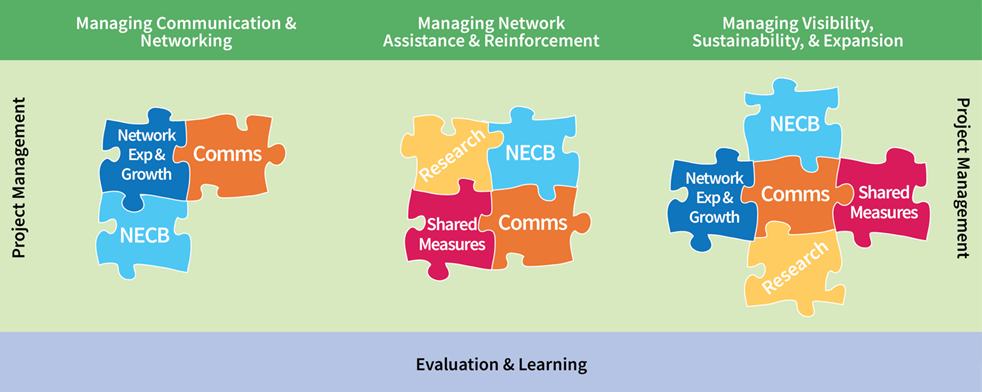

The different task areas, as demonstrated below in Figure 1, interlock with each other like puzzle pieces to support the Coordination Hub goals, and align with project management and evaluation and learning.

Under each task area, organizational representatives form sub teams to perform the activities. This model is beneficial to share the workload, ownership, and accountability among each organization. At the same time, it creates a culture where the task teams collaborate with each other to achieve the broader goals of the Coordination Hub and to break down silos.

Figure 1. Structure of NSF INCLUDES Coordination Hub

Note: Network Exp & Growth: Network Expansion & Growth; Comms:Communications; and NECB: Network Engagement and Capacity Building

Relationships and relevant experience unite the organizations

Our introduction into the initiative was natural since several partner organizations, including ours, had forged strong working and professional relationships while serving as technical assistance providers for NSF INCLUDES prior to the Coordination Hub’s formation. We collaborated with Coordination Hub partner organizations on presentations at professional conferences and in past evaluation projects.

The strength of these interlocking relationships enabled us to join the Coordination Hub seamlessly. Our credibility and external expertise in collective impact and strategic communications were already established without needing formal initiation. Over time, we developed personal bonds; as individuals from each partner organization have built strong working relationships, so has our collective ability to support the INCLUDES National Network. Shared vision and values emerge from the personal relationships that we have forged.

Shared vision, values, and responsibilities align the work

The Coordination Hub’s values and principles—focusing on a commitment to systems change through continuous learning, service to vision and mission, and embodying the commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion—align with those of each partner organization. Our compatibility is a unifying thread, given different ways of working and areas of expertise among the partners. In addition, the Coordination Hub partners balance expertise in STEM and in collaborative change strategies, such as collective impact, with expertise in shared measures and metrics, network engagement, communications, and research.

Complementary skills and knowledge enhance learning and knowledge creation

Each organization brings its own “ways of working” and general content and methodological expertise to the initiative, while deploying staff throughout different task areas to strengthen the creation and dissemination of knowledge throughout the INCLUDES Network.

Partners and teams form across organizations to balance content and methodology, which strengthens the product quality—for instance, collaborating on the development and communication of research briefs focused on underrepresented populations in STEM, like people with disabilities, and girls and women; and developing, conducting, and promoting webinars for Network members on shared goals and metrics, and leadership and communication. The dynamic enriches the partnership—team members complement each other when producing these products and briefs, creating richer content applicable to Network members.

Conclusion

The Coordination Hub’s development enables similarly structured initiatives to consider organizational approaches to the common goals. Creating opportunities for increased collaboration among the task areas—such as centering our collective work for the coming year around the theme of systems change to broaden participation in STEM—and working toward common goals enabled the Coordination Hub to transition from a siloed structure to a more cohesive and interdependent partnership.

Our model demonstrates that innovation and implementation is better when there are multiple, diverse perspectives represented—whether those come from a diverse Hub team with a variety of experiences and expertise, or whether those come from thoughtful engagement of Network members to inform the work.

While the work can be “messy,” with each partner bringing different organizational cultures and areas of expertise to the engagement, the group has navigated these tensions to mesh into one that is aligned in its approach and unified in the goal of helping build a National Network that will accelerate broadening participation in STEM education and careers.

We welcome a conversation on how you have engaged in multi-partner initiatives. What was your experience in these structures, and how did you navigate different organizational cultures and ways of working to help build stronger collaboration?